Americans are Becoming Less Punitive

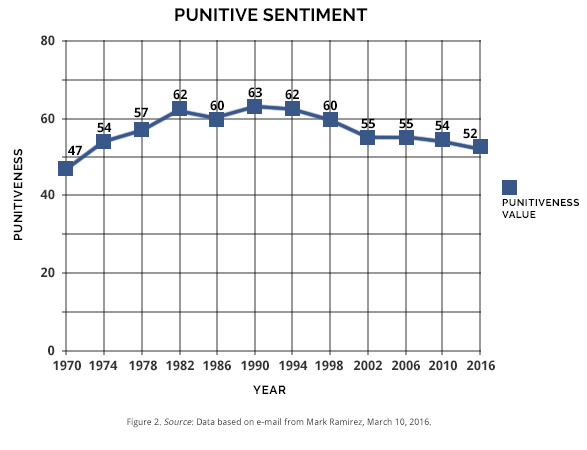

After 40 years of public support for harsh criminal justice policies, public opinion research points in the direction of a significant thaw that could, over time, produce an actual paradigm shift, away from punitiveness and towards prevention, rehabilitation, and reintegration as corrections policy goals. According to one group of scholars, “a turning point in public punitiveness appears to have transpired.” Political scientist Mark D. Ramirez has constructed a way to measure what he calls “punitive sentiment,” defined as “the aggregate public support for criminal justice policies that punish offenders.” He examines trends in the responses to four questions relating to different punitive policies that have been asked repeatedly over time by public opinion researchers: support for capital punishment, tougher judicial sentencing, increasing the authority of law enforcement, and increasing spending for tougher police enforcement. By plotting these four indicators across time, a pattern emerges. According to his analysis, punitive sentiment began to increase in the mid-1970s and reached its apex in the mid-1990s. It has been on a downward trajectory ever since, and today punitive sentiment is about where it was in 1973, before the era of “law and order” took firm hold.

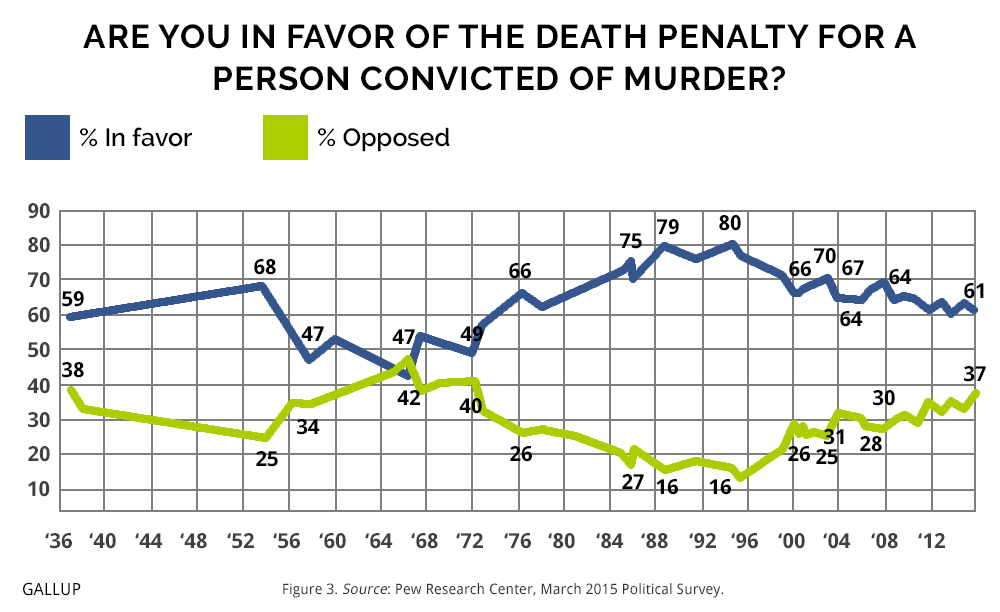

A softening of punitive sentiment since the mid-1990s is reflected in the responses to questions that have been repeatedly included in national surveys such as the General Social Survey and the Gallup Poll. In 1994, a full 85 percent believed that “courts do not deal harshly enough with criminals.” By 2014 that number had dropped 27 points to 58 percent. Support for the death penalty has also dropped substantially, although it is still favored by a majority of Americans. In 1994, 80 percent said they favored the death penalty for a person convicted of murder and only 16 percent were against it. By 2015 that figure had dropped to 61 percent with 37 percent opposed. In 1994, 63 percent of the public thought the country was spending too little money on law enforcement. By 2014 only 46 percent thought so, an all-time low.

The decline in punitive sentiment over time can be seen in how Americans identify the main purpose of prisons and the criminal justice system. In 1994 an ABC News Poll queried, “What do you feel is the main purpose of prisons. Is it to… keep criminals out of society, punish criminals, or rehabilitate criminals?” Fifty-three percent chose incapacitation (keeping criminals out of society), 29 percent chose punishment, and only 16 percent chose rehabilitation. According to The Opportunity Agenda’s Opportunity Survey, 20 years later when asked how society would be better served by the criminal justice system, 54 percent chose “stricter punishment for people convicted of crimes” but 46 percent chose “greater effort to rehabilitate people convicted of crimes” reflecting a significant evolution in public attitudes. The groups most supportive of rehabilitation as a goal are blacks (59 percent), Asian Americans (53 percent), people between the ages of 18 and 29 (53 percent), Democrats (56 percent), and people with college and post-graduate degrees (52 percent and 66 percent, respectively).

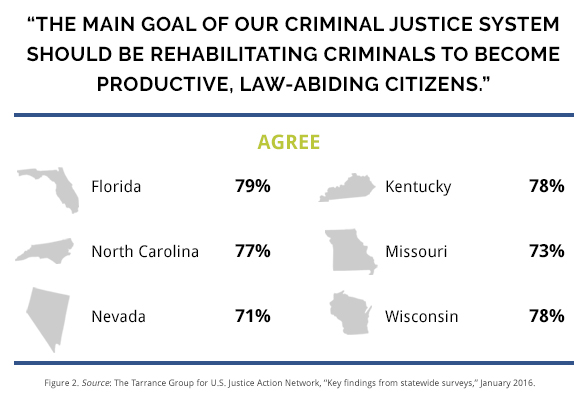

According to several state surveys, in recent years the goal of rehabilitation has moved to the top and punishment as the principal goal has fallen out of favor. When asked what they thought should be the “main emphasis in most prisons,” 53 percent of Oregonians chose rehabilitation, compared to 37.5 percent who chose “protect society” and only 9 percent who chose “punishment.” In early 2016, voters in six states overwhelmingly agreed with the following statement:

Massachusetts residents were asked, “Which do you think should be a top priority for dealing with crime?” and given four choices. A plurality of 43 percent chose “prevention, such as education and youth programs,” followed by “rehabilitation, such as education and job training for prisoners” (21 percent), “punishment, such as longer sentences and more prisons” (15 percent), and “enforcement, such as putting more police on the streets” (19 percent).

Polling on specific criminal justice issues supports the notion that punitive sentiment is on the decline. Following are recent surveys on data points Ramirez uses in his punitive sentiment scale.

The Death Penalty

As noted above, support for the death penalty for people convicted of murder is the lowest it has been since the mid-1970s. These changes in only 19 years—from 1996 until 2006—are substantial.

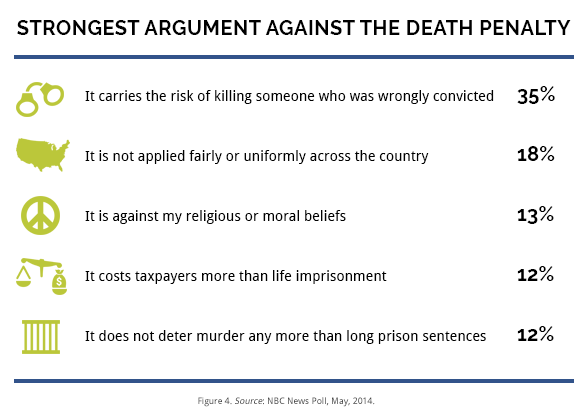

There is evidence that a major reason for the drop in support is the public’s concern about wrongful convictions. In a 2014 survey by the NBC News Poll, respondents were asked to choose what they believed was the strongest argument against the death penalty. A plurality of 35 percent chose “it carries the risk of killing someone who was wrongly convicted,” compared to only 13 percent who cited moral reasons:

Pew Research Center also probed the reasons people had for support or opposition to the death penalty by presenting respondents with two statements, and asking them to choose the one most similar to their views. As in the NBC News Poll, the opposition message that scored the highest had to do with innocence. When asked between the following statements, 71 percent chose the first, and only 26 percent chose the second:

- 1. There is some risk that an innocent person will be put to death.

- 2. There are adequate safeguards to ensure that no innocent person will be put to death.

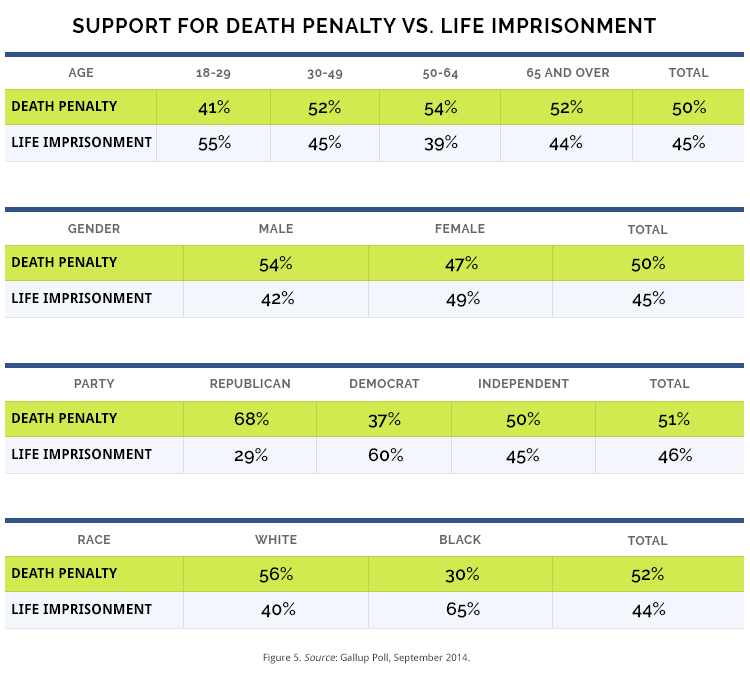

Support drops even further when respondents are given the choice between the death penalty for murder and life imprisonment “with absolutely no possibility of parole.” Fifty percent choose the death penalty and 45 percent choose life imprisonment. There are significant differences based on age, gender, party affiliation, and, especially, race:

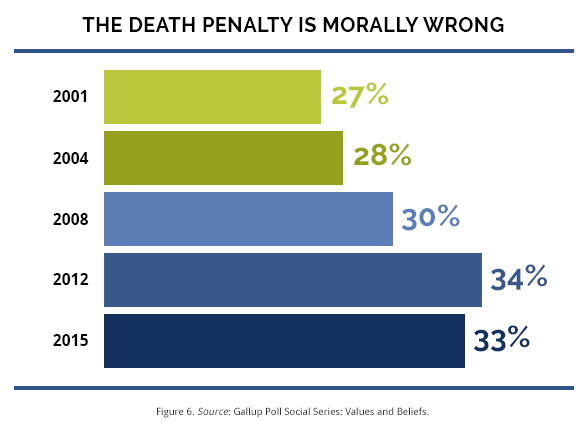

Opposition to the death penalty on moral/religious grounds is still a minority view and has remained fairly stable over the past 15 years.

Most Americans today do not believe the death penalty deters people from committing serious crimes; only 35 percent believes it does, while 61 percent believes it does not. A majority of Americans (52 percent) agrees that people of color are more likely than whites to be sentenced to the death penalty for committing similar crimes.

Sentencing Laws

Although a majority of Americans continue to believe that courts do not deal harshly enough with “criminals,” support for that idea has dropped significantly over the past 20 years. In 1994, 85 percent thought the courts were not harsh enough; by 2014, that had dropped to 58 percent. There are other signs that support for draconian sentencing, a hallmark of the law and order years, is on the wane. In 1994, at the height of the “war on crime,” California voters approved the “Three Strikes” Initiative by a margin of 72 percent to 28 percent. An attempt in 2004 to reform the law narrowly failed, by a vote of 53 percent to 47 percent. Finally, in 2012, California voters overwhelmingly voted in favor of Proposition 36, which revised the Three Strikes law to impose a life sentence only when the new felony conviction is “serious or violent” and made approximately 3,000 people serving life sentences eligible for resentencing.

Recent surveys show that Americans disapprove of mandatory sentences at least for “nonviolent offenders.” The Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) asked whether respondents agreed or disagreed with the following statement: “Mandatory minimum prison sentences for nonviolent offenders should be eliminated so that judges can make sentencing decisions on a case-by-case basis.” Seventy-seven percent agreed (35 percent “completely agreed” and another 42 percent “mostly agreed”).

There is also broad support for eliminating federal mandatory minimum sentences. A nationwide survey conducted in January 2016 for the Pew Charitable Trusts posed the following question:

“As you may know, mandatory minimum sentences require those convicted of certain crimes to serve at least a certain length of time in prison. Some people have proposed that instead of mandatory minimums judges have the flexibility to determine sentences based on the facts of each case. Would you find this proposal generally acceptable or generally unacceptable?”

A very substantial majority of 77 percent said they would find it “acceptable.” It is notable that the question did not use the term “nonviolent,” nor did it define what those “certain crimes” were. The result suggests a strong preference for judicial discretion when it comes to sentencing regardless of the crime, and this is true even among Republicans, 60 percent of whom found it “acceptable.”

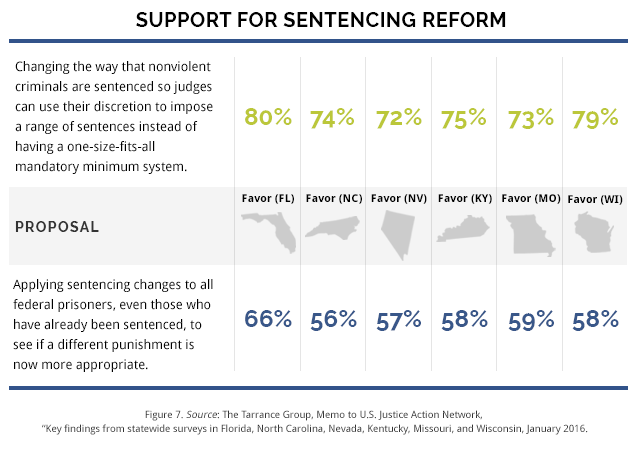

A series of state polls reveals that support for judicial discretion and reform of mandatory sentencing laws is widespread and exists in both red and blue states. Voters in Florida, North Carolina, Nevada, Kentucky, Missouri, and Wisconsin were presented with two proposals for sentencing reform, and both proposals received majority support. The first proposal is limited to “nonviolent criminals,” but even the second proposal which applies to “all federal prisoners” receives majority support.

A Virginia survey showed that 64 percent of that state’s adults agreed that “sentencing should happen at the local level so the judge can use his or her discretion based on the particulars of the case.”

It is in the area of sentencing for drug crimes that the biggest shift in public opinion has occurred. After being presented with statistics showing that nearly half the people in federal prison are there for drug crimes, 61 percent of voters believe “too many drug criminals are taking up too much space in our federal prison system. More of that space should be used for people who have committed acts of violence or terrorism.” According to a national poll commissioned by the ACLU, the belief that “drug addicts and those with mental illness should not be in prison, they belong in treatment facilities,” is almost universal: 87 percent agreed with that statement.

Attitudes towards marijuana law enforcement began to change in the early 2000s. According to the Gallup Poll, by 2015, 58 percent of Americans supported legalization, including 71 percent of 18 to 34 year olds. Not only that, the public has a sense of inevitability about full legalization: 75 percent think the sale and use of marijuana will eventually be legal nationwide.

Support for easing up on criminal sentences has begun to apply to other illicit drugs as well. In February 2014 the Pew Research Center asked respondents:

“Some states have moved away from the idea of mandatory prison sentences for nonviolent drug offenders. Do you think this is a good thing or a bad thing?”

Sixty-three percent said it was a “good thing” and 32 percent said it was a “bad thing.” When the same question was asked in 2001 the numbers were 47 percent and 45 percent, respectively. Attitudes about drug sentencing have changed radically just in the past decade. Three state polls administered by the Drug Policy Alliance in early 2016 show the same trend towards the decriminalization of drug use, even in a conservative state like South Carolina. In response to the question:

“Some people think we should treat drug use as a health issue and stop arresting and locking up people for possession of a small amount of any drug for personal use. Do you agree or disagree with this sentiment?”

South Carolina voters agreed by a margin of 56 percent to 32 percent; New Hampshire voters by a margin of 73 percent to 16 percent; and Maine voters by a margin of 63 percent to 29 percent.

Too Many People in Prison

Another sign that the public’s “punitive sentiment” is waning is the growing recognition that too many people are in prison at too great a cost. A nationwide survey commissioned by the ACLU of voters likely to vote in the 2016 presidential election revealed that 69 percent thought it was “important for the country to reduce its prison populations,” including 81 percent of Democrats, 71 percent of independents, and 54 percent of Republicans. Significantly, of the voters who said reducing the prison population was important, a plurality of 39 percent said the main reason was “because sentences are disproportionately severe” as compared to “because the cost of prison is too high” (29 percent). The survey also showed that the prospect of a reduced prison population did not generate fear in the vast majority of respondents. When asked to choose between the following two statements, 58 percent chose the first and only 29 percent the second:

- 1. Reducing the prison population will help communities by saving taxpayer dollars that can be reinvested into preventing crime and rehabilitating prisoners.

- 2. Reducing the prison population will harm communities because criminals who belong behind bars will be let out.

Even voters who reported having been a victim of crime and were threatened with physical harm (17 percent of respondents) were as likely to support reductions in the prison population as voters overall.

Two recent state polls had similar results. A 2014 survey of Massachusetts residents asked: “Do you think there are too many people in prison in Massachusetts, not enough people in prison, or is the number of people in prison about right?” A plurality of 40 percent said there were too many, 27 percent said about the right amount, 17 percent said not enough, and a relatively large segment, 16 percent, said they didn’t know. When asked whether it would be preferable to build more prisons or reform the system so fewer people are sent to prison, 67 percent chose reform and only 26 percent chose prison building. A survey conducted in December 2015 showed that 75 percent of Virginians thought that the prison population was costing too much money and that 62 percent agreed that “too many people are in prison for nonviolent crimes.”

Crime and Criminal Justice Reform Are on the Public’s Radar

In its most recent Religion and Politics survey, conducted in January 2016, the Pew Research Center asked the following question for the first time:

“I’d like to ask you about priorities for President Obama and Congress this year. As I read from a list tell me if you think each should be a top priority, important but lower priority, not too important, or should not be done: reforming the criminal justice system.”

Forty-four percent said it was a top priority and 39 percent said it was an important but lower priority. Since the question has not been asked previously, it is impossible to see a trend, but the fact that 83 percent of respondents believe it is either a top or important priority, ahead, for example, of “dealing with global trade issues,” suggests that criminal justice reform is on people’s minds and has some traction. Responses varied by race and political affiliation, with 73 percent of blacks and 48 percent of Latinos ranking it as a top priority compared to 39 percent of whites. Nearly half of Democrats (49 percent) said it was a top priority, compared with 32 percent of Republicans.

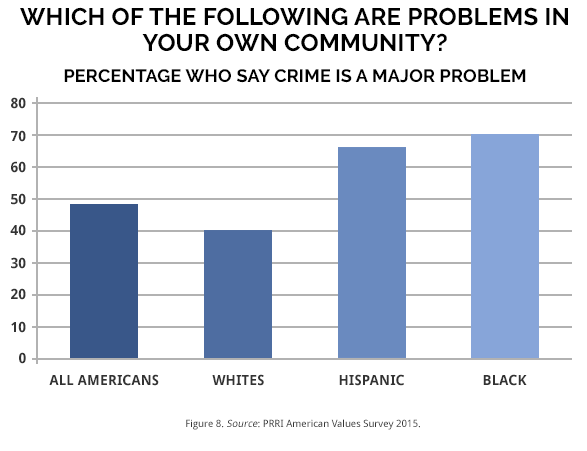

The level of concern about crime also varies by race and ethnicity. When asked “how important are the following issues to you personally,” 53 percent say it is a “critical issue,” rating it higher in personal importance than the growing gap between rich and poor (48 percent), climate change (34 percent), and race relations (39 percent). But salience is much higher among black and Latinos. As the graph below shows, 40 percent of whites rank crime as a “major problem” in their community, as compared to 70 percent of blacks and 66 percent of “Hispanics”.