Challenges

While the overall trends are favorable to change, there are some red flags that advocates should be aware of.

Fear

Fear of crime and victimization has long been recognized as a driving force behind Americans’ attitudes towards criminal justice policy. In general, fear has a strong positive effect on support for punitive crime policies. A study examining the impact of fear on public preferences for allocating resources to rehabilitative versus punitive criminal justice policies found that if an individual is more fearful of crime, his or her odds of preferring rehabilitative policies are reduced by 40 percent.

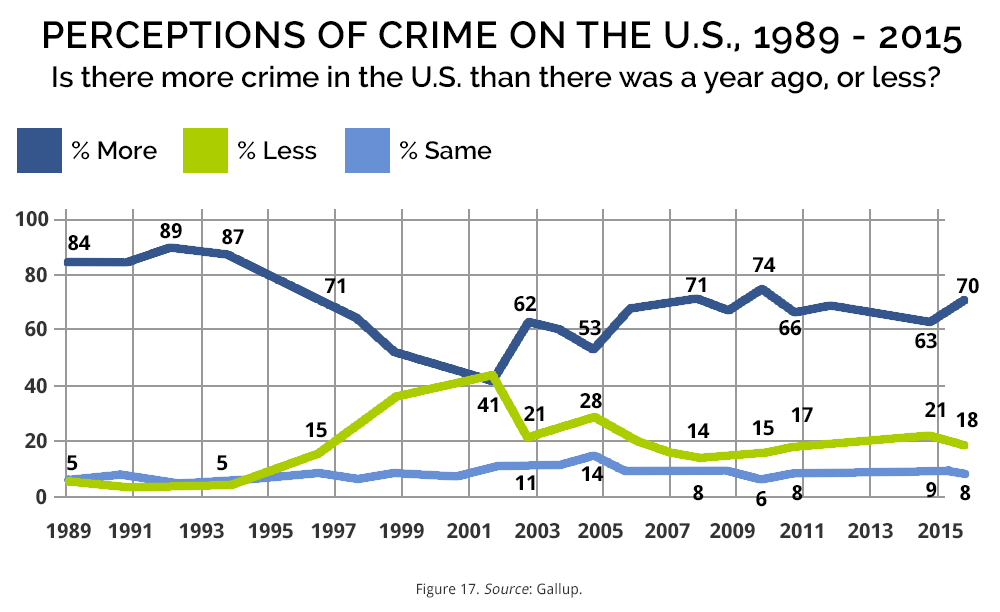

In spite of the widely reported drop in the crime rate year after year since it reached its peak in 1994, according to Gallup’s annual Crime Poll, a majority of Americans believe there is “more crime in the U.S. than there was a year ago.” Gallup suggests that the seven-point increase from 2014 to 2015, from 63 percent to 70 percent, may be a function of “people reacting to news reports of increased violent crime in many major U.S. cities.” Crime may be down, but the homicide spike in Chicago, for example, received national media coverage, and mass shootings during this period seemed to occur with frightening regularity.

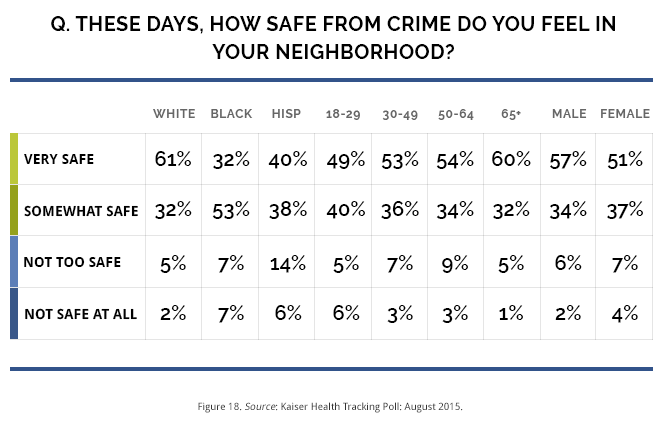

Americans overall are more sanguine about the safety of their own neighborhoods, and the perception that crime is worse nationwide than it is locally has been the case historically. But significant segments of the public do worry about crime in their local area, and according to PRRI’s American Values Survey, concern appears to be rising. In September 2012, 33 percent of respondents said crime was a “major problem” in their own community; by October 2015, that number had gone up to 48 percent. An August 2015 Kaiser Health Tracking Poll asked, “These days, how safe from crime do you feel in your own neighborhood?” Fifty-four percent said “very safe,” but another 36 percent said “somewhat safe” and 10 percent said either “Not too safe” or “Not safe at all.”

How safe one feels in his or her own neighborhood varies significantly by race and ethnicity, and by age (gender differences appear to be less significant).

THE RACIALIZATION OF CRIME

A great deal of scholarship has been devoted to the ways in which race influences Americans’ attitudes about crime and punishment, and the consensus is that crime in America is racialized, i.e., experienced by whites (and others) in racial terms. Recent public opinion research probing attitudes on the relationship between crime, race, and ethnicity, however, is sparse. Nazgol Ghandnoosh, Ph.D., of the Sentencing Project, explains that there are two types of questions survey researchers have used to measure the “racial typification of crime”:

One approach has been to ask respondents to estimate the racial composition of specific crimes. These studies consistently show that Americans, and whites in particular, significantly overestimate the proportion of crime committed by blacks and Latinos… The second approach to measuring racial perceptions of crime draws on the General Social Survey (GSS). Produced by NORC at the University of Chicago, this long-running survey has asked respondents to rank various racial and ethnic groups on a scale ranging from “tend to be violence-prone” to “tend not to be prone to violence.” … On a scale where 1 refers to not violence-prone and 7 refers to violence-prone, non-Hispanic whites on average rated whites at 3.70, Hispanics at 4.20, and blacks at 4.48.

The NORC question, however, has not been asked since 2000. We have identified one more recent study that tests what criminologists call the “racial threat theory”: the extent to which whites support punitive criminal justice policies and social control of blacks because they view blacks as a criminal threat. The goal of a study conducted by a group of criminologists at Florida State University was “to understand the often observed relationship between neighborhood racial composition and the perceptions of criminal threat by white residents by examining the extent to which the latter is explained by or contingent on the racial typification of crime.” The researchers found that perceived neighborhood racial composition was positively related to perceived victimization risk among white Americans, and that changes in composition were especially threatening. Fear of victimization was significantly higher among those respondents who reported that the number of blacks living in their neighborhood had increased in the past five years. They concluded:

In sum, the current study shows that perceived Black population growth increases perceptions of victimization risk among Whites who hold stereotypes of Blacks as criminals… Stated differently, the evidence suggests that the stereotype of Blacks as criminals, to the extent that perceptions of victimization risk translate into pressure on authorities to control crime, may serve to both mobilize Whites and justify controlling responses in the context of Black population growth.

THE INTERSECTION OF IMMIGRATION AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE ON ATTITUDES TOWARDS LATINOS

The term “crimmigration” was coined by law professor Juliet Stumpf in a law review article published in 2006. The term reflects the intersection and increasing entanglement of two systems: criminal justice and immigration enforcement. Current immigration enforcement, with its emphasis on the identification, arrest, detention, and deportation of “criminal aliens” by local law enforcement, has blurred the line between immigration control and criminal justice. There is evidence that crimmigration has affected Americans’ assessment of “Latino threat” and increased their support for aggressive policing and profiling.

Based on data collected in 2010, criminologist Justin Pickett tested two hypotheses:

- 1. Perceptions of Latino economic and political threat will be positively associated with support for expanding police investigative powers.

- 2. The relationship between perceived Latino threat and support for expanding police powers will be strongest in the case of investigative powers, such as police profiling, that have the clear potential to result in discrimination against Latinos.

The results of Pickett’s analysis bear out both hypotheses: the perception of political and economic Latino threat is associated with support for expanded police powers among white respondents, and the relationship is most pronounced in attitudes towards police profiling. The study shows that even among whites who understand that discrimination will result in aggressive policing of Latinos, increasing anxiety about Latino threat trumps that concern.

THE “VIOLENT” VERSUS “NONVIOLENT” LABEL

The frequent labeling of crimes as “violent” or “nonviolent” in the public discourse may have created an unhelpful dichotomy in the minds of most Americans that reduces support for sentencing reform. It has also affected the framing of questions in recent public opinion research. In their Policy Essay, “Public Opinion and Criminal Justice Reform: Framing Matters,” criminologists Kevin M. Krakulich and Eileen M. Kirk comment on Thielo et al.’s study, “Rehabilitation in a Red State” (see p. tktk) and point out that the study

focuses on public support for reforms addressing nonviolent and/or drug offenders. Only approximately one-fifth of the growth in state prison populations can be explained by the increase in drug incarceration, whereas violent offenders explain more than half of the growth. Thus, it is significant that Thielo et al. find, at least, that support for treatment over prison remains for repeat offenders, but if we choose only to focus on them, we are missing a large piece of the reason for prison growth, and we will have a reduced impact on the system at large.”

There has been minimal research exploring support for reform in the context of “violent” or “serious” crime, but what little there is suggests that while punitive sentiment has declined when the subjects are described as “nonviolent” (often coupled with “drug offenders”) or “first-time offenders” or people convicted of “low-level crimes,” that might not be the case when it comes to those deemed “violent” or “serious” or “repeat offenders.” The label further stigmatizes an already stigmatized population.

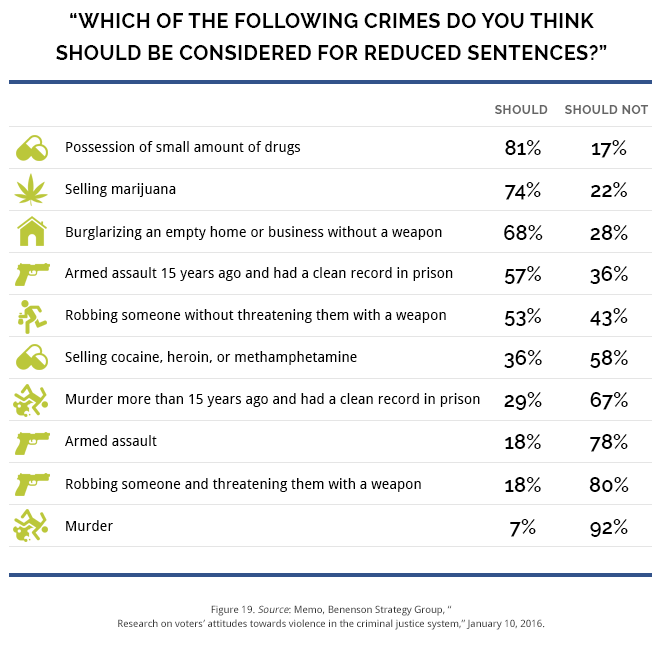

In June 2015, the ACLU commissioned research on attitudes towards reducing sentences for “violent offenders” which found that using the word “violent” is “a buzzword that pushes voters away from supporting reforms.”. But when the researchers tested support for reduced sentences for specific crimes, a potentially important finding emerged. As the chart below shows, the information that someone convicted of armed assault committed the crime “fifteen years ago and had a clean record in prison” significantly increased support for a reduced sentence for that individual.

The researchers concluded:

In short, there is undoubtedly hesitation to support criminal justice reforms for violent offenses, which voters believe warrant time behind bars. But focusing on the offenders, rather than the crime, could provide a potential path forward. Specifically:

- Voters’ belief that even serious offenders can change

- Violent offenders who have served time and had a clean record in prison could be considered for reduced sentencing.

- A clean record in prison plus the completion of rehabilitation programs demonstrates a commitment to change in the eyes of voters.

They recommend shifting the conversation from the offense to the “offender.”

SYSTEMIC VERSUS INDIVIDUAL CAUSES OF CRIME

There is little recent data on what Americans currently think about the root causes of crime. The question was most recently asked in an explicit way in 2006 in a survey by the National Center for State Courts. At that time, when presented with a list of five possible main causes of crime, Americans favored two individual causes, choosing either drugs (33 percent) or the breakdown of the family (26 percent) as the major factor. “Poverty” was not included in the list; the closest offered was “unemployment” which was chosen by only 10 percent. Clearly as of 10 years ago, the public overall did not have the same understanding of the intersection of crime, poverty, and racism.

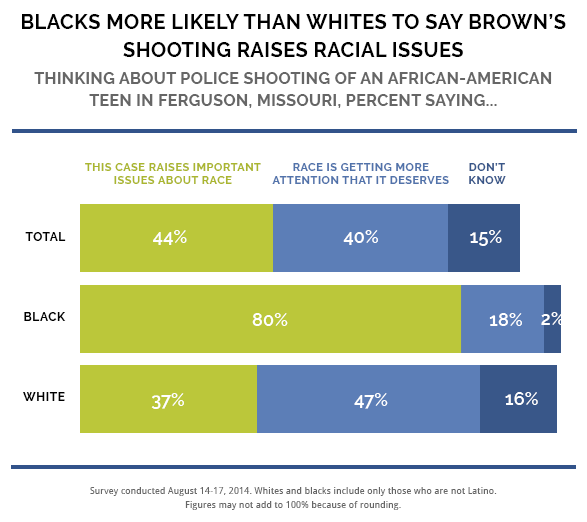

Several more recent questions about policing show that black Americans and, to a lesser extent, Latinos, have a clearer understanding than whites that race and class intersect to produce discriminatory outcomes. When asked if the grand jury decisions in Ferguson and Staten Island were “isolated cases and do not reflect an overall problem with the justice system when it comes to race and police officers,” 33 percent of whites said “no” compared to 76 percent of black Americans and 56 percent of Latinos. As the chart below shows, blacks were more than twice as likely as whites to say the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson raised “important issues about race.”